MIA houses some of the most beautiful and historic Qur’an manuscripts from the Islamic world. The following images offer a sneak peek at five of these treasured Qur’an manuscripts.

The Museum of Islamic Art (MIA)’s impressive collection of manuscripts ranges from the famous Abbasid Blue Qur’an, which is known as one of the finest and rarest manuscripts in the Islamic world, to pages from the largest Qur’an in the world, the Timurid Baysunghur Qur’an.

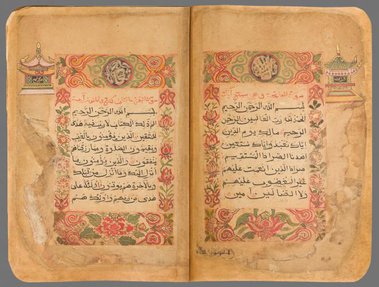

Folio from a Timurid monumental Qur'an manuscript, Uzbekistan (Samarkand), 9th century AH/15th century CE, Gold, black ink, and opaque watercolour on paper, Sura Al-‘Ankabut (“The Spider”), vv. 25-27

Written in elegant muhaqqaq script, this page is from the largest medieval Qur'an ever made. For a long time, it was known as the “Baysunghur Qur'an”, named after the illustrious Timurid prince and art lover, but more recently, it’s believed that it was produced for his famous grandfather, the ruler Timur (r. 1370–1405 CE) himself. Only dispersed folios of the manuscript survive. Once complete, it would have required 1,600 pages and 2,700 square meters of paper to contain the full text of the Qur’an.

Allegedly, the manuscript was prepared by the one-armed calligrapher Umar-e Aqta, who first spent years producing a miniature Qur'an that would fit into a ring. When he presented this proudly to Timur, the great ruler thought the small size unworthy of the Qur'an. Relentlessly, the calligrapher then set about producing the largest Qur'an manuscript ever seen and presented it to Timur, who this time granted the appreciation the artist sought. Monumental Qur’an manuscripts were considered both signs of piety and powerful political statements for their affluent patrons.

(The Timurid Empire was a Persianate empire, which included all of Iran, modern Afghanistan and modern Central Asia. It was formed by the Turco-Mongol conqueror Timur.)

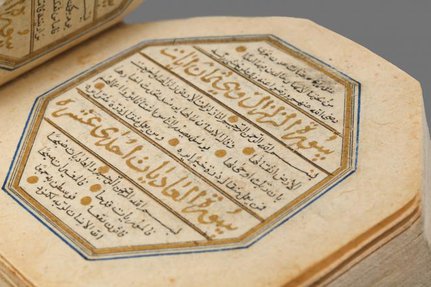

Miniature copy of the Qur'an, Iran (Shiraz), 10th century AH/16th century CE, Gold, ink, opaque watercolour on paper and leather binding

Miniature Qur’ans had an important protective function for their carriers; small pieces of parchment with Qur’anic passages rolled in small pendants were used as early as the first centuries of Islamic history. Written in a flawless minute script known as ghubari (meaning “dust”) with a sharp nib, this miniature Qur’an might have served its owner more as a protective device than an actual book to consult. The manuscript would have originally fit into a small octagonal box with loops and hooks to be carried around, tied on the upper arm with strings or sewn on clothes or robe lining.

A Qur’an manuscript from Southeast Asia, Java, 13th–14th century AH/19th century CE, Ink and opaque watercolour on paper

The division of the text of this manuscript into juz’ (parts), which are indicated by two semicircular arcs in the outer vertical margins of the two facing pages, suggest that this manuscript originates from Java. Qur’an manuscripts produced in Islamic Southeast Asia present very distinctive and bright illumination; in particular, manuscript production in Java displays such a mesmerising variety of styles and shapes of illuminated decorations that it is challenging to fit them into one single category. This manuscript opens and closes with two pairs of decorated frames that combine a variety of elements, vegetal motifs, architectural details, and sets of floral spikes around the margins in different combinations, making up a lovely and colourful effect.

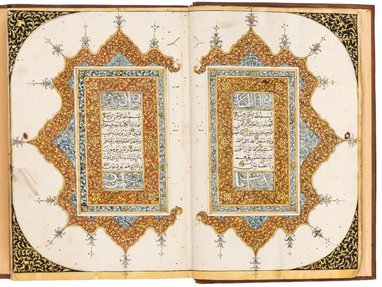

Complete Qur’an manuscript, China, 11th–14th century AH/17th–19th century CE, Gold, ink, and opaque watercolour on paper

This manuscript is a fine example of Qur’an production in China, most likely produced during the Qing dynasty (1644–1911 CE). It is written in a variant of muhaqqaq script known as sini (“Chinese”), distinctive to that region. The verses are marked with red circles or dots, and the chapter headings are in red ink indicating the surah and the number of verses. The two pages shown are the opening pages of the Qur’an; the page on the right is Surah al-Fatiha (“The Opener”) and on the left Surah al-Baqara (“The Cow”).

The pages are beautifully bordered with Chinese floral motifs using vibrant colours such as red, green and gold to stand out. The Chinese pagodas are what make this manuscript unique as well. The words within the pagodas on each corner say Qur’an Kareem (“noble Qur’an”).

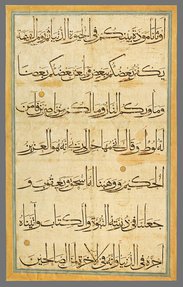

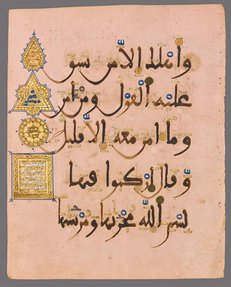

Folio from the so-called “Pink Qur’an”, Southern Spain or Morocco, 7th century AH/13th century CE, Gold, ink, and opaque watercolour on pink-dyed paper, Surah Hud, vv. 40-41

This folio comes from an Andalusian Qur’an manuscript known as the ‘Pink Qur’an’, named after the colour of its paper. Each page contains five lines of text copied in dark brown ink with diacritical marks and verse markers in gold paint and diverse opaque watercolours. This manuscript is an exquisite example of how the maghrebi script had evolved. Maghrebi script has distinct features, such as large, round curved letters, and is usually written in dark brown or black ink with gold illuminations. The script was first developed in Al-Andalus and the Maghreb region — hence the name.

This rare example of dyed pink paper was probably produced in the city of Jativa (in what is today southeastern Spain), where the site of the earliest Spanish paper mill is located. The use of paper is an innovation for Andalusian manuscripts, as parchment was still the most common writing support used for Qur’ans during that time in the Iberian Peninsula.

You May Also Like

Read

Collection Highlight: Sitara of the Ka‘ba

Read

Collection Highlight: The Damascus Room

Read

Collection Highlight: The Shahnameh