Q: What was the inspiration behind the Your Ghosts Are Mine: Expanded Cinemas, Amplified Voicesexhibition and how did the title come about?

Matthieu Orléan: The show was first showcased at the ACP-Palazzo Franchetti in Venice to coincide with the 60th International Art Exhibition at the Venice Biennale.

I was invited by Qatar Museums (QM) and the Doha Film Institute (DFI) to create something that reflects QM and the DFI’s deep engagement with moving images—both cinema and video art. I know there are a lot of films that are on the side of independent cinema for DFI, and they produce movies from the Middle East, North Africa, Southeast Asia—in countries where it is often difficult to produce movies on your own due to lack of public funding. These movies are not always broadcast in theatre, and it was a big challenge and a responsibility to highlight these art pieces, in the context of the Venice Biennale.

The Biennale that year had a strong focus on the global South, offering space to voices outside the Western world. So, I think it was quite interesting to create a dialogue between different worlds, civilisations and artists. I was very much inspired by this project because it was transnational and very wide in spirit.

The title, Your Ghosts Are Mine, came later. It took a lot of time to go through all the movies and videos, and then, I realised that the ghosts were hidden everywhere and could definitively be at the center of the show. So, the title came quite spontaneously, quoting indirectly a dialogue from one of the movies presented in the exhibition, named Zanj Revolution by Tariq Teguia (2015).

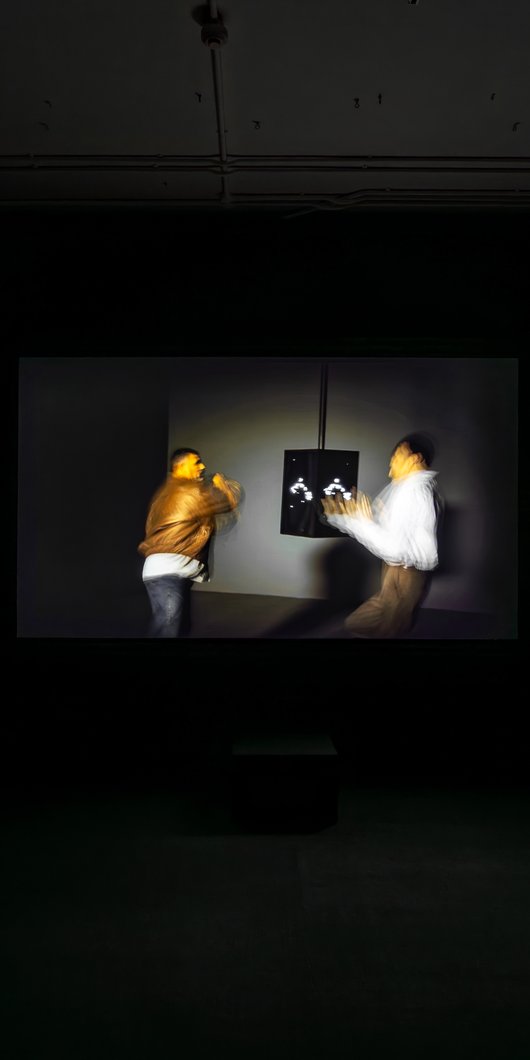

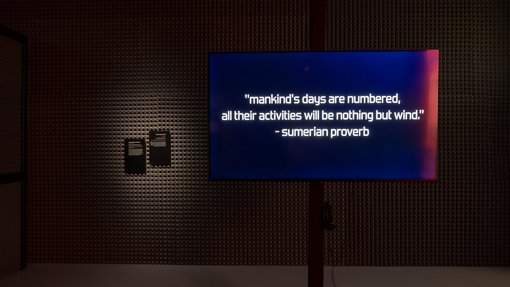

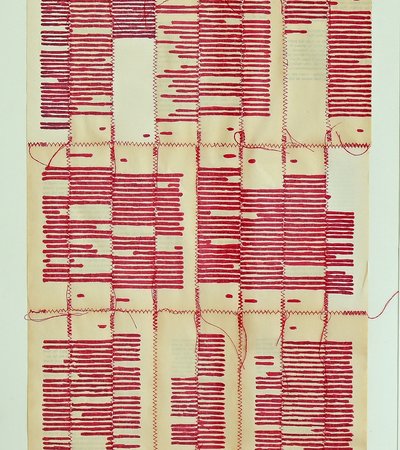

I like the title for many reasons. There are many ghosts or djinns in the old ruins of the deserts (for instance like in The Dam by Ali Cherri, or in the video installation by Wael Shawky named Al Araba Al Madfuna III). They could be seen as a metaphor of your ancestors and your traditions (like the supernatural blast shaking the young heroine of Al-Sit by Suzanna Mirgahni). They could be compassionate sometimes, but if you listen too much to them and lose contact with your fellow humans, you could be led to madness and violence (like in Abou Leila by Amin Sidi-Boumédiène). The ghost has multiple faces.

I also like the idea of a phantom limb, meaning that something is both present and not present. In a way, never complete.

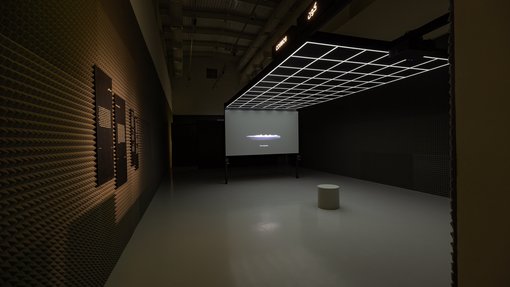

From a curatorial perspective, a Phantom limb is like hidden thematics, something that you can't really go through or express, but shape the project. That’s part of the emotional texture of the exhibition, especially in the Doha exhibition, where you begin with a spiritual, archaeological vision of the desert and you end with desert 2.0, which is a desert seen through the lens of the future with Sophia Al Maria’s beautiful video pieces.

I was very interested in the word ghost, as it is also from a movie and I thought it would be good to have it in the title and I came up with Your Ghosts Are Mine, and the idea of the words you and mine being a mirror.

It was quite interesting showcasing the idea of an inspiring dialogue between two people that could be the artist and the audience, the curator and the artist, and anyone else at the show.