Q. What do you think visitors will find most surprising about the exhibition?

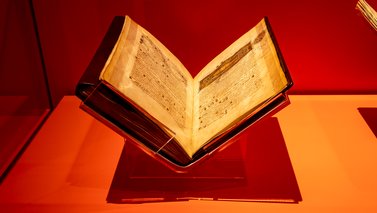

Abudaya: People might be surprised to learn that Morocco had a significant impact on Islamic science and theology, more than we often realise. It’s easy to view the Western Islamic world as somewhat marginal. However, if we consider figures like Ibn Khaldun, who was from present-day Tunisia but lived most of his life in Morocco, we see a major historian in Islamic history. When people learn that the Qarawiyyin in Fez is the longest-functioning university in the world, established in the 9th century, they’ll recognise its importance to Islamic history overall. This connection will resonate with people here regarding the Islamic history of Morocco.

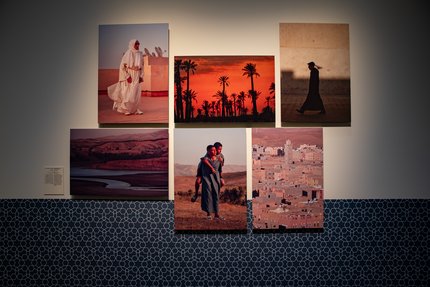

They may also be surprised to see some contemporary pieces, especially the last one. When thinking about traditional heritage, many might not expect to encounter a contemporary art piece that showcases the aesthetics behind traditional craftsmanship and how it can be reinterpreted and reused through contemporary work.

Additionally, they might be taken aback by the colours in the exhibition. We’ve designed the space with bold exhibition elements that differ from what we’ve had before. We aimed to use shiny and vibrant colours that represent Morocco in a modern way. So, I believe people will be surprised because we’ve never had anything like this at MIA.

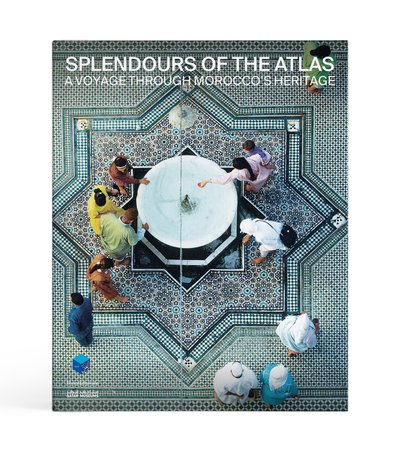

Q. In addition to works from MIA's permanent collection, this exhibition includes loans from several other entities, including Morocco and other QM partners. How do the loaned objects shed new light on MIA's collection? What kind of conversations or dialogues are sparked by bringing all these works together in one place?

Abudaya: From Morocco, we have the National Foundation of Museums, which includes many museums across the country. Our goal was to represent most of these museums in the exhibition. We have objects from the Kasbah Museum of Mediterranean Cultures in Tangier, the Museum of History and Civilisations, the Oudayas Museum, and the Mohammed VI Museum in Rabat. In Fez, we have pieces from the Dar Batha Museum, the future Museum of Islamic Art, due to open very soon, and from Meknes, the Dar Jama‘i Museum, which focuses on music.