The city of Samarra at the banks of the River Tigris (nowadays in Iraq), was one of the most extraordinary cities of its time. Founded by the Abbasid caliph al-Muʿtasim in 221 AH/ 836 CE, Samarra served as the temporary capital of the Abbasid caliphate until 279 AH/ 892 CE, when the caliphs returned to their former capital of Baghdad.

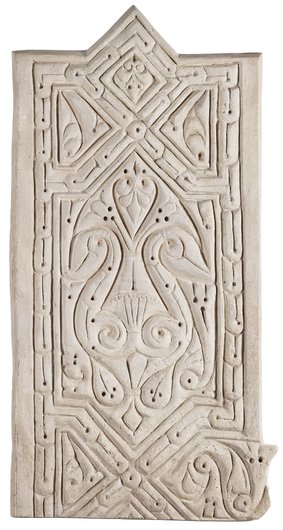

The Abbasids turned their new cities of power into– what we would label today– a ‘Silicon Valley’. Thanks to the vigorous patronage of the Abbasid caliphs, these cities quickly turned into important cultural and commercial hubs, attracting scholars and thinkers from all over the Islamic world. From vast engineering projects to artistic and technological innovations to great developments in the fields of learning and science, the Abbasids set new architectural and artistic trends and scientific standards; their prolific art industry prompted important technological innovations in glass, ceramic and stucco industries.