Walking into the exhibition One Tiger or Another, I found myself thinking of Edouard Glissant. In his book Poetics of Relation (1990), Glissant argues for a right to opacity for everyone — against the rigidity and reductiveness of the illusion of absolute understanding. He argues that even when we accommodate for difference amongst people and cultures, we still attempt to reduce things to make them transparent, a function of our desire to ‘understand’ difference. But this reduction depends on an inherent hierarchy, since it measures difference against a scale — a notion of a norm — which can then be used to make judgements. What is needed instead, Glissant writes, is opacity: the opaque is not the obscure, it is that which cannot be reduced.

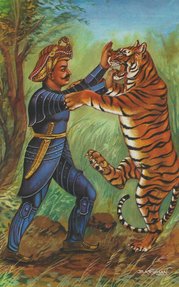

One Tiger or Another, curated by Tom Eccles and Mark Rohan Rappolt, is an exhibition that navigates histories that refuse to be reduced or immobilised, constantly shifting and reinventing themselves. Conceptualised as part of the inaugural edition of Rubaiyat, a quadrennial exhibition series that takes a multidisciplinary approach to ‘overlapping realities and truths and the ways in which those who are muted or without a voice make their truths heard’— One Tiger or Another is a story about how stories can be retold, and how they shape our shifting histories. The exhibition takes us into the world of two tigers. We encounter Tipu Sultan (Sultan Fateh Ali Sahab Tipu, 1751–1799), celebrated across history as the ‘Tiger of Mysore’, brought to life in the exhibition space through a combination of historical and contemporary objects that map the shifting narrativisations of him as either a hero or a villain.

Tipu Sultan’s legacy is subject to immense debate and political contestation — some describe him as India’s first freedom fighter, others would label him a despot. Leftists hail his resistance against colonial rule, Hindu nationalists declare him to be a tyrant. The shifts in the stories about him have mirrored shifts in history and power. One Tiger or Another archives these dynamics in material terms – and transforms them into a spatial experience that you can step into and navigate.