Souq Al-Hamidiyah

An enduring meeting place for people, goods and ideas from all over the world, the souq is, and has been, a core part of daily communal experience – a continuation of shared activities under one roof from market to mosque and home.

Standing at the heart of Damascus, one of the world’s long-inhabited cities, Souq Al-Hamidiyah has stood witness to the city’s turbulent history.

Sunlight streams through bullet holes in its iron canopy, erected by the Ottomans, as a testament to the 1920s conflict between the Syrians and French Colonists. Throughout the ongoing war, the Souq has escaped damage.

The thriving commercial heart of the historic city, the souq has welcomed merchants from far and wide, with goods exchanging hands and travelling out across the Indian Ocean World and beyond.

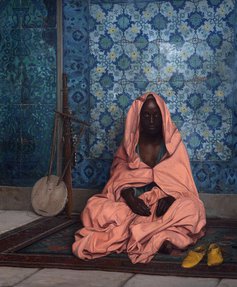

As bustling and dynamic meeting places, souqs have featured regularly in the works of Orientalist artists.