Design for a New China

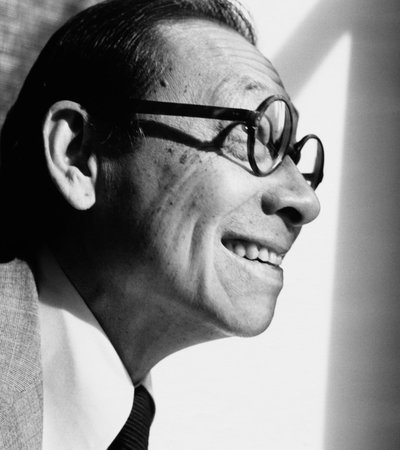

Pei grew up in Hong Kong, Shanghai, and Suzhou during the tumultuous Republican era. This, coupled with his training in the United States, shaped his aspirations to develop a new, modern vision for projects connected to China.

Pei’s integration of formal and spatial elements from historical architecture in China was not just a nostalgic re-reading of the past. His interpretation and application of traditional Chinese architecture and garden design, informed largely by his experience of growing up in Suzhou, had continued to evolve throughout various project types. From the design of a university campus to a terraced water garden framing the site of a tower, Pei’s work reveals his consistent yet dynamic incorporation of visual, spatial, and philosophical characteristics of historical Chinese environments without neglecting present needs and methods in modern architecture as society and technology advance.

Tunghai University (1954–1963), Taichung

After 1949, the organisation behind Huatung University engaged Pei to design Tunghai University. Pei was still working for Webb & Knapp in New York City, so he enlisted Chinese architects Chang Chao-kang and Chen Chi-kwan to manage design details and construction. Tunghai’s design of interweaving interior and exterior spaces reflects Pei’s pursuit of harmony between nature and the built environment, which underpins much art and architecture in China. The asymmetrical layout of sloped roof structures clustered around a courtyard with covered walkways was influenced by vernacular Chinese architecture. However, the campus design also includes a main axis typical of American universities, as well as an inventive use of prefabricated reinforced concrete and timber-frame construction.

Expo ’70 Taiwan Pavilion (1969–1970), Osaka

Kuomintang politicians saw Taiwan as the custodian of Chinese culture. Because of this, they had a strong preference for obvious Chinese architectural features, like palatial, upturned roofs. However, the Taiwan Pavilion at Expo ’70 was a departure from this tendency. As a jury member for the pavilion’s design competition, Pei was invited to further develop the winning proposal, which resulted in a taller structure comprised of two triangular concrete blocks of galleries. They were connected by criss-crossing tubular bridges around a four-storey atrium. Pei convinced authorities to accept the design, claiming that its shifting perspectives and simple exterior, which enclosed a more complex, unfolding sequence of spaces, echoes the experience of a traditional Chinese garden.

Bank of China Tower (1982–1989), Hong Kong

To work with the challenging site of the Bank of China, Pei incorporated a terraced Chinese garden design to give the difficult site a more dignified framing. He included a rock-and-water garden plaza on cascading slabs along a steep slope at the base of the tower. Their triangular shape echoes both the tower’s angled profile and its granite base. A pool begins at the upper southern entrance and continues along two terraced basins on opposite sides of the building, creating a loop. The landscaped spaces also served to address concerns that the building’s sharp angles create inauspicious feng shui.

Suzhou Museum (2000–2006), Suzhou

Suzhou Museum is in the city’s most historic quarter, adjacent to the 16th-century Humble Administrator’s Garden. Its design also incorporates an existing 19th-century mansion. Pei’s careful intervention draws from the surrounding areas, echoing the form, scale, and materiality of the neighbouring urban fabric. The result is a complex of whitewashed plaster walls and dark-grey granite roofs, situated half underground to ensure the museum remains lower than its surrounding structures.

Miho Museum (1991–1997), Shigaraki, Shiga

Pei’s design for the entryway towards Miho Museum is inspired by the Chinese fable ‘The Peach Blossom Spring’ written by poet Tao Yuanming in the fifth century. In the story, a fisherman discovers a hidden passage through a grotto that leads to an idyllic land. For visitors to Miho Museum, their first view of the building comes at the end of a tunnel, framed by the cables of a suspension bridge spanning a ravine. As most of the museum had to be built underground, its glazed roof structure, a tetrahedral space frame composed of carbon-steel tubes, allows natural light into the building. Its silhouette of peaks and valleys also echoes nearby Edo-period farmhouses.

Deutsches Historisches Museum (1996–2003), Berlin

After Germany’s reunification in 1989, Pei was commissioned to design an extension to the German Historical Museum in Berlin, housed in the Zeughaus, a historic building. Located near Museumsinsel, an island of cultural complexes, the new wing would be mostly hidden from the city’s grand boulevard Unter den Linden. As was often part of his process, Pei carefully considered the surrounding landmarks when designing the building’s entrance: visitors would walk along this main road and pass Karl Friedrich Schinkel’s Neue Wache memorial before reaching Museumsinsel. Pei designed the new wing as a triangular building in limestone with a glass-and-steel hall, contrasting with its neighbours and offering views of the surrounding historical landmarks. To maintain the character of the nearby alleyways, Pei built an underground pathway between the Zeughaus and the new wing.

Musée d’Art Moderne Grand-Duc Jean (MUDAM) (1989–2006), Luxembourg

Intrigued by the prospect of building something new on the foundations of an eighteenth-century fortress, Pei selected the grounds of Fort Thüngen as the new site for a modern art museum in Luxembourg. In Pei’s plan, the museum follows the fort’s arrow-like layout, but preservationists opposed his initial proposal to have visitors enter through the historical fort. After some revisions, which included moving the entrance to the back of the complex, the museum was completed 17 years later, in 2006. Its glass facade, airy central spaces, and glass bridge provide direct views onto the historical fort and the city centre below, putting the old in dialogue with the new.

Museum of Islamic Art (MIA) (2000–2008), Doha

The Museum of Islamic Art (MIA) in Qatar presented Pei with the challenge of finding a design anchor to reflect its rich collection of Islamic art across continents and multiple centuries. After studying Islamic architecture from different times and places, Pei was drawn to the Mosque of Ibn Tulun in Cairo, Egypt, which was completed in the ninth century. The design of the mosque’s domed sebil, a fountain for ritual washing, progresses from an octagon to a square and finally to a circle, a geometric logic that was culturally and historically specific yet also universally coherent. Its simplicity was also appropriate for Qatar, which did not have a particular architectural tradition for a building of this scale.

Fragrant Hill Hotel (1979–1982), Beijing

Set among the forests of a former imperial hunting ground, Fragrant Hill Hotel has a meandering floor plan that evokes the visual and spatial unfolding of a classical Chinese garden. Upon entering the forecourt, visitors have a north-to-south sightline through the courtyard lobby to the main garden outside. The hotel’s corridors and guest rooms are all carefully arranged to have views of the hotel’s smaller gardens, which feature ancient tree varieties set against white walls. Pei referenced Chinese architecture while integrating modern structures, most significantly the space truss in the lobby roof.