Concrete Visions

Concrete is a mix of cement, air, water, sand, and gravel. It has been used in building and construction for thousands of years. In the mid-1800s, builders began using steel-reinforced concrete, largely due to its ability to support both straight and curved forms.

As concrete gained popularity in reconstruction efforts after the Second World War, Pei’s office began experimenting with cements, sands, and aggregates across America, exploring the material’s applications as a structural component and an interior or exterior finish. Pei’s team played around with setting times, pouring and vibrating techniques, and surface treatments, ultimately refining the use of a material known for its colour inconsistencies, cracking, and sensitivity to changes in temperature. They also employed concrete as a cheaper alternative to stone. In projects such as the National Gallery of Art (NGA) East Building, Pei explored how concrete can complement marble and achieve structural efficiency.

Kips Bay Plaza (1957–1962), New York

In the face of strict budget constraints, Pei turned to structural concrete for New York’s Kips Bay Plaza. At the time, structural concrete was typically used for highways and other large-scale infrastructure projects. Pei’s team conducted extensive research on the material and developed an innovative, lightweight concrete mixture that was both facade-worthy and load bearing. Kips Bay Plaza became a prototype for other low-cost housing projects.

National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) (1961–1967), Boulder, Colorado

Pei looked to the nearby cliff dwellings of the Ancestral Puebloan peoples—which look like they grow out of their natural setting—to design the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in a way that would harmonise with the surrounding landscape. These structures at Mesa Verde National Park inspired NCAR’s blocky, hooded towers and keyhole windows. Pei opted for a raw, bush-hammered finish on the concrete across the complex’s two tower clusters. The technique exposes the reddish-brown stones that make up the concrete, creating blush-red hues that unify the building with the nearby Flatirons rock formations.

Dallas City Hall (1966–1977), Dallas, Texas

Pei’s challenge when designing Dallas City Hall was how to provide sufficient space for all the municipal departments. Although public-facing offices required the least space, Pei wanted to situate them on the ground floor for easy visitor access, which led to the building’s inverted pyramid form. Each floor of the building extends 2.8 metres further out than the one below, creating a facade with a dramatic inward slope. The exposed concrete was a response to the city’s restrictive budget. The design also includes an innovative post-tensioning system and uses a newly developed concrete that minimises cracking, which typically occurs during the curing process.

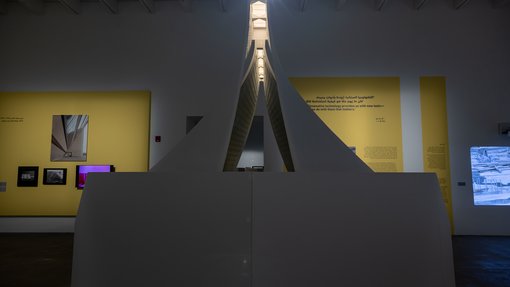

Luce Memorial Chapel (1954–1963), Tunghai University, Taichung

Pei intended for the Luce Memorial Chapel to be the centrepiece of Tunghai University. In its realised design, the building’s roof resembles the hull of a wooden ship. Made of four separate panels, the roof has narrow skylights where the panels converge. The roof’s complexity requires the use of a lattice-like structure of reinforced concrete. With the material change from an original timber design, local contractors had to meld contemporary concrete construction techniques with long-standing building practices for wood and bamboo.

Glass and Steel

In addition to working with reinforced concrete and stone, Pei was also skilled at leveraging the properties of glass and steel to construct buildings that appeared transparent and light while maintaining structural efficiency, a minimalist aesthetic, and monumentality in the design.

Pei began experimenting with glass-and-steel structures in the 1950s, working with new construction technologies and expert engineering collaborators. His design for the skylight atrium of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., completed in 1978, marked his first successful application of glass and steel as building and roof enclosures.

National Gallery of Art (NGA) East Building (1968–1978), Washington, D.C.

For the National Gallery of Art (NGA)East Building, Pei wove together form, structure, and material to create a modern extension that references the older West Building. Pei used the same stone—Tennessee pink marble—for exterior cladding, and a similarly rosy-hued exposed concrete for the interior. To create a visual and spatial relationship between the buildings, he mirrored the imposing presence of the West Building’s masonry structure. The jointless knife-edge prow on the front facade, which gives the building its iconic triangular form, also captures this sense of solidity in the old building. The triangular element is further emphasised by a three-dimensional glass skylight over the atrium.

Polaroid Tower (1969; unbuilt), Cambridge, Massachusetts

Pei designed this 45-storey building for the Polaroid Corporation’s new headquarters in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Never realised, the Polaroid Tower’s design utilises exterior bracing that resembles the grid-like covering of industrial gas storage tanks. The building’s structural system, made up of diagonally and horizontally arranged steel beams, wraps around the glass enclosure and eliminates the need for interior support columns.

Bank of China Tower (1982–1989), Hong Kong

Pei’s graceful, tapering designs for the Bank of China Tower in Hong Kong satisfied both a need for structural strength and a desire for visual prominence. To withstand earthquakes and meet local wind load requirements, the building is designed with criss-crossing diagonal supports that connect five main columns, one in the centre and four at the corners of the building. This three-dimensional structural system is reflected in the striking pattern of interlocking diamonds along the building’s facade.

Grand Louvre (1983–1993), Paris

Pei’s vision for the Louvre Museum specified a structure that would respect yet break with architectural tradition. Pei pursued the glass pyramid as his optimal form: it is structurally stable, and its tapered shape minimises any visual obstruction of its historical neighbours. To further reduce the architectural disruption, Pei strove to make the pyramid, in his words, ‘as transparent as technology would allow’. The resulting design uses a steel frame built from a system of parts in simultaneous tension and compression, which supports an extra-clear glass skin. Both features are achievements that spurred innovation in the wider architectural and manufacturing world.

Miho Institute of Aesthetics (MIA) Chapel (2008–2012), Shigaraki, Shiga

Pei sought to make this chapel a focal point in the campus of the Miho Institute of Aesthetics (MIA). Pei devised the chapel’s teardrop-shaped design, which can be modelled by simply bending a fan-shaped strip of paper until the ends meet. However, translating this conical form into an architectural structure proved challenging until it was generated using geometric calculations. The chapel’s insulation and acoustic requirements necessitated a concrete structure, but Pei achieved its curved, sculptural effect by wrapping the building in stainless-steel panels produced by Japanese manufacturer Kikukawa, which now produces such panels for Apple stores globally. Inside the chapel, red panels mask the structural shell, producing a quiet environment for contemplation and meditation.

Hyperboloid (1954–1956; unbuilt), New York

Hoping to revive an ailing rail industry, the nearly bankrupt New York Central Railroad invited Pei to reimagine its Grand Central Terminal in the mid-1950s. Pei responded with a 456-metre-high building dubbed the Hyperboloid, a tubular structure with flared ends. The design features diagonally intersecting columns that form an exoskeleton structure so efficient that it requires the same amount of steel used for the Empire State Building, which is twenty per cent smaller. The Hyperboloid is Pei’s first skyscraper design, although it was never built.

Pei Residence (1952), Katonah, New York

In 1952, Pei designed and built a rural retreat for his family in Katonah, New York. In Pei’s reinterpretation of modernist glass houses, deep verandas enclosed by fixed and movable glass panes surround the bedrooms, bathrooms, kitchen, and interior living areas. The approach creates a house-within-a-house that adapts to the area’s cold winters and hot summers. Pei also used the cross-layered wooden beam construction of Chinese temples in the house’s foundation, making the building appear to float above its landscape.

Helix (1948–1949; unbuilt), New York

Pei’s first project for Webb & Knapp was the unbuilt Helix apartments. For its design, Pei stacked wedge-shaped, split-level units into a column that spiralled up twenty-one storeys. Its unusual concentric design would give tenants the flexibility to join multiple units together and expand or contract their living space as desired. Although the building was unrealised, William Zeckendorf, the head of the firm, patented the innovative design.

A Collaborative Process of Invention

When Pei joined real estate company Webb & Knapp in 1948, developer William Zeckendorf provided him with resources to build a team. This became the foundation of Pei’s own office, as he brought over a seventy-person architectural team to form I. M. Pei & Associates (later I. M. Pei & Partners, then Pei Cobb Freed & Partners) in 1955. Pei was skilled at identifying and developing his staff’s expertise and fostering a shared design language and work culture. Pei’s office was known for its collaborative practice, material and technological research, and pursuit of excellence. At its peak, the office housed its own cement collection, stone library, and a model shop to create miniature architecture.

Geometry of Pei

Buildings designed by Pei are known for their striking geometric forms. Pei often experimented with geometry to address issues ranging from site limitations to structural requirements. The triangle was a foundational element for the Louvre Pyramid in Paris and the Bank of China Tower in Hong Kong. In buildings like the Suzhou Museum and the Museum of Islamic Art (MIA) in Doha, Pei combined simple shapes to create more complex polygonal forms. These structures are not only visually engaging, but also remarkable feats of engineering.